March, the month of women, and also of solutions to the climate crisis

Photo credit: Earth Negotiation Bulletin, 2010

By Taís Serra Montani, Researcher at EmpoderaClima.

Solutions to the climate crisis demand representation: the inclusion of diverse groups in society, especially those on the front line of the impacts of environmental disasters. Representation is effective in solving the climate crisis, as it increases the possibilities and expands the perspectives of solutions. In celebration of March, the Women’s month, we bring the perspective of gender equity based on the history of female leadership in previous COPs, expectations for the COP29, and upcoming institutional arrangements on climate.

Greenpeace Brazil carried out a survey and revealed that, in 28 editions of the Conference of Parties, only 5 of them were chaired by women (representing only 21% of female leadership in global negotiations); these specific COPs were in the years 1995, 1998, 2010, 2011 and 2019. This data is alarming for the effectiveness and results of the negotiations, since women, as they are often on the front line of climate disasters, have experience and/or live in communities that are already developing techniques and everyday solutions for climate consequences already noticeable in different regions of the world.

Mary Robinson, in her book Climate Justice, points out that approximately 70% of the food consumed on the planet is produced by thousands of small farmers located on the African and Asian continent, with more than half of these farms led by women. It is too naive to think that all these business leaders do not have ideas that can be applied to the rest of the world, or even have contributions on the climate cause and its effects, especially when we take in consideration that their businesses depend on climate conditions.

“Not including women at the decision-making and debate tables at the biggest conference on climate ends up being a way of slowing down the creation of solutions to the crisis.”

We are witnessing a constant percentage of women in the delegations that arrive at the COPs. At COP26 in the United Kingdom, women occupied less than 33% of all positions in subsidiary bodies, a trend that had been repeated since COP24 (Katowice, Poland). In 2022, at COP27 in Egypt, the number increased to 34% - that remained in the 28th edition, in Dubai. For comparison purposes, in 2008 (COP14, Poznan, Poland), the composition of women as delegates was 31%. As much as we have major decisions about gender being made at the event, women are not the majority in defining the plans.

COP1 (Germany, 1998)

Related to the presidency of conferences, those led by women made very important advances, which deserve to be highlighted. In 1995, through Angela Merkel (former German Chancellor), negotiations began to reduce CO2 emissions in developed countries, recognizing the relevance of the action taken by the northern hemisphere in light of the history of degradation in its industrialization and exploration processes of natural resources. This year, the first UN Climate COP took place in Germany, and it is an honor to see history being made with a woman at the center of the decision-making table.

COP4 (Argentina, 1998)

In 1998, efforts to ratify and implement the Kyoto Protocol were centralized. The presidency was granted to Maria Julia Alsogaray, former Minister of Natural Resources of Argentina. The Kyoto Protocol was the first major step towards allowing countries to be open to commitments at the international level regarding environmental degradation - this step being taken with a woman presiding over the debates is certainly an achievement that needs to be recognized. It is important to highlight that treaties take many years to be, in fact, concluded. COPs that consolidate their signatures are truly successful editions.

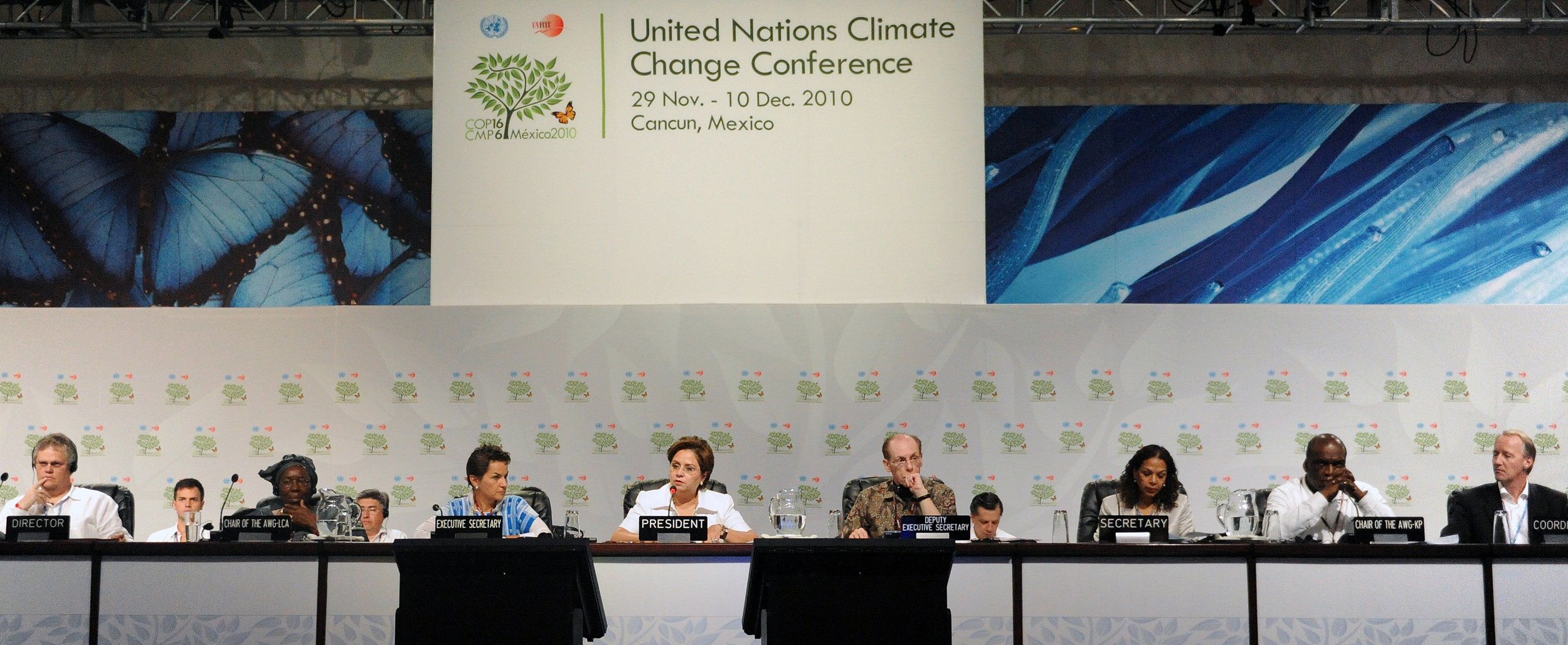

COP16 (Mexico, 2010)

With a gap of more than 10 years, it was only in 2010 that a woman was the main figure at the conference: Patrícia Espinosa, former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Mexico. Its COP brought together the signing of several treaties, among them, demands from developed countries regarding compensation for disasters and for the front line (Green Climate Fund). This information is highly relevant, since the climate financing agenda, raised more frequently in recent editions, has already been addressed since 2010.

It is important to remember that, in 2016, Patrícia also assumed the position of Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). She remained in the position until 2022 and is highly recognized for her years of experience with governance supported by gender equality, human rights, and sustainable development policies.

COP17 (South Africa, 2011)

In 2011, COP17 was chaired by Maité Nkoana-Mashabane, former Minister of Women, Youth and People with Disabilities of South Africa. The meeting gave life to the Durban Platform, a document that brought together a series of actions to break the increase in global average temperature. Here, a major international agreement was being rehearsed that could replace the Kyoto Protocol. Therefore, the Platform was an important step towards defining the goals that would be the focus of the next treaty.

COP25 (Madrid, 2019)

Finally, 2019 was the stage for Carolina Schmidt, Chile's Minister of Environment at the time, who brought the approval of a new Gender Action Plan. It was an edition that enabled the focus on oceans, science and agriculture - themes that began to be brought up in the most recent editions and lack global attention, in addition to having characteristics that need to be eventually explored.

We can see that women as presidents of the event do an exceptional job, making it possible to point out relevant progress in all the editions that have had their leadership.

The Greenpeace survey also reminds us that the famous Paris Agreement was designed by a woman: Christiana Figueres. A Costa Rican diplomat with extensive experience in public policy and climate change, she shared an experience negotiating the agreement in her book co-written with Tom Rivett-Carnac, titled The Future We Choose: Surviving the Climate Crisis. She held the position of Executive Secretary of the UNFCCC from 2010 to 2016 - being one of the most influential women in climate diplomacy today.

Source: Observatório do Clima

Another important architect of the Paris Agreement is Laurence Tubiana, a climate finance activist in the reformulation of global governance. She is the CEO of the European Climate Foundation, a philanthropic organization focused on social empowerment and reducing emissions. Her highlight comes at COP21, when not only is she at the negotiating table for the biggest climate agreement in history, but she is also named UN Climate Change High-Level Champion - a title given to major influences in the fight for a more resilient planet.

All of these women were essential to build solutions in the history of the COP, being crucial even for the execution of one of the biggest steps taken to date in the history of the climate fight - the Paris Agreement itself.

Regarding 2024, civil society received the terrible news that the organizing committee of COP29, which will take place in November this year in Azerbaijan, was entirely made up of men. Initially, 28 men made up the event's cast, but they were extremely criticized by important figures who pointed out the setback that this represented for the climate fight since it does not only affect 50% of the population. Christiana Figueres called it “unacceptable and shocking” after so many advances in recent years. Then, 12 women were added to the board to contain criticism. The number is still far from equal for the organization and representation of the conference.

We hope this year will bring more awareness in the spaces of negotiation and debate, mainly through gender parity. We remember that every month should be loaded with the success of women who were and are global, regional, and, of course, local leaders. We hope to continue encouraging them so that they can occupy the spaces that so desperately need their perspectives, knowledge, and representation.